Full article in eJewishPhilanthropy.com, August 31, 2023. [Below includes just the first and last paragraphs] https://ejewishphilanthropy.com/hebrew-learning-in-synagogues-a-call-for-change/ No need to go running for the ice buckets, but I’m officially throwing out a challenge to all involved in synagogue/part-time Jewish education to lower the emphasis on, and decrease the amount of time devoted to Hebrew decoding. We are a quarter of the way into the 21st century, but still holding onto a last-century Hebrew-learning goal — the fluent and accurate “reading” of Hebrew prayers. No, I’m not suggesting that we stop teaching the Alef-Bet, nor Hebrew decoding skills. Rather, I am challenging us to expand our Hebrew learning goals... [The middle part of the article offers info from research on teaching reading, as well as Jewish historical realities that explain why we need to change our focus. Go read it!] Hebrew has the potential to touch our children’s hearts if we expand our learning goals, moving beyond an almost singular focus on prayers. I challenge educators and clergy to invite stakeholders to new conversations about Hebrew learning goals and to reconsider their assumptions about successful Hebrew learning. I also challenge colleagues to discover ways to create a more symbiotic relationship between Hebrew recitation and decoding. If a child can recite/sing G’vurot, can we not count that as an equal success to decoding it? And once a child can recite G’vurot, how can we help them complement their oral mastery of the blessing with the printed words on the page? This is relatively new territory – it needs all of our brain power. The gauntlet has been thrown down! On behalf of our learners, will you accept the challenge? ***** Rabbi Andrew Ergas, director of Hebrew at the Center, took the theme from the article above one step further in his own eJP opinion piece the next week: https://ejewishphilanthropy.com/its-time-for-teshuva-for-hebrew-education/. His words can inspire us to consider how else we can be connecting our learners to Hebrew, whether within or beyond our doors.

0 Comments

At its core, #OnwardHebrew is a grassroots initiative that supports sound-to-print Hebrew learning in part-time synagogue settings. The rest, as we say, is commentary. It is not formal curriculum, nor a prescribed list of do's and don'ts, but an approach based on the research of how children learn languages sound-to-print. #OnwardHebrew had its beginning about ten years ago when several education directors began chatting about their frustrations with Hebrew "reading" skills of children who completed sixth grade. Informally, the directors committed to piloting experiments that could change assumptions about Hebrew learning in part-time/synagogue settings. In the fall of 2017, they gathered in Cleveland to share successes, challenges and hypotheses for future efforts. From this beginning, #OnwardHebrew launched. Five years later, what have we learned?

You don't have to go it alone!

#OnwardHebrew started with innovators who were willing to experiment and share their successes and challenges. Early adopters soon followed. In these initial stages of development, the initiative worked on growing its cache of "existence proofs," stories that answer the question, "does this really work?" Five years later, #OnwardHebrew has not only grown its base, but education directors and synagogues across North America happily share their own stories of success and satisfaction. If #OnwardHebrew won't work for your educational program, that's fine, really. But if you are intrigued and find yourself questioning or struggling, don't give up too early! A change process takes time and benefits from outside support. How can we help? Nachama Skolnik Moskowitz, on behalf of the #OnwardHebrew Leadership Team  For decades, teachers have been told that students produce better answers when the teacher asks a question and then waits 3 seconds before asking a clarifying question or saying something else. The 3 seconds of "wait-time" gives learners time to process their thinking and produce a response. But here's another application of wait-time ... I just read a recently published study that reports on the importance of having students learning new vocabulary wait 2-4 seconds before repeating a new word aloud. And why? “When a person repeats a word immediately after hearing it, cognitive resources are dedicated to preparing the production of the word and, as a result, these resources cannot be used to deeply encode that word. In contrast, if production is delayed for a few seconds, this overlap is avoided, allowing deeper learning and encoding to take place." So, I'm wondering a couple of things related to #OnwardHebrew:

I don't have answers to these two questions (nor do I know what this 2-4 second wait time would look like for the decoding process), but maybe someone would find this interesting to explore in their teaching. If you do, let us know what you discover via the #OnwardHebrew Facebook group! Nachama Skolnik Moskowitz  I'm not sure where the phrase "breaking teeth" originated, but it has been used to describe the painful process of decoding, letter-by-letter. For decades, when new Hebrew learners (whether children or adults) have been asked to read aloud and the process is usually very very slow and laborious - they "break their teeth." But, of course, I'm here to tell you that there's a better way! At the foundation of sound-to-print learning is the principle that people need to know the sounds of a language prior to tackling the print. For #OnwardHebrew, on a macro level that includes being introduced to Hebrew Through Movement, Jewish Life Vocabulary and regular t'fillah. However, on a micro level, when working on decoding, learners can be given cues that preview the sounds for them. Why? It offers them some of the tools that they automatically have gained in their native language. Our Hebrew prayers, blessings, and texts like Torah and Haftarah were written 2000 years ago. The complex language and grammatical forms are difficult even for Hebrew native language speakers. Our new learners are at an even bigger disadvantage since they can't self-correct when decoding - think about the challenge when they see unfamiliar words like: וְשנַּנְתָּם לְבָנֶיךָ. So, instead of asking students to "sound out" a Hebrew word or phrase, we help them tremendously when we "cue" them in the four ways noted on the embedded image. How can teachers learn to do this? 1) Share and discuss this short video that explains easy-to-implement "cueing up" teaching strategies: tinyurl.com/Sound2Print. 2) Offer copies of the "four strategies" image. Right click on it and either download ("Save As") or Copy. Then, paste the image into a document and print for easy reference. Alternatively, check the "Files" in the #OnwardHebrew Facebook group for a downloadable copy of higher resolution. 3) Experiment with the "cues" and have conversations with colleagues to tweak your practice! Questions or comments? Please share them on the #OnwardHebrew Facebook group.  #OnwardHebrew just published a very helpful (and relatively concise!) getting started booklet that offers assistance to educational leaders looking to adopt/adapt the sound-to-print principles of #OnwardHebrew in their educational program. The booklet answers such questions as:

In addition, there are What-Why-When-Who quick peeks offered for each of the four elements of #OnwardHebrew - Hebrew language (Hebrew Through Movement), Jewish Life Vocabulary, Hebrew t'fillah and the introduction of decoding after children have built the sounds of Hebrew (for "in" programs, that is in fifth grade or later). Interspersed are QR codes with links to short videos that provide extra information. And, as if that's not enough, there's a curated set of other resources - just enough to get an education program started, without being overwhelming. So, what do YOU want to know?  By, Nachama Skolnik Moskowitz This blogpost is a response to an August 5, 2022 posting in the JEDLAB FB group, sharing a lengthy article by Saul Rosenberg. In it, Rosenberg offered an analysis of the challenges of teaching "fluent Hebrew reading in Hebrew School" and hinted towards a solution he is working on. To understand my blogpost, it would be helpful to first read/skim the original article. I apologize in advance for the length of my own response, but as you'll see, it hit a lot of buttons. Rosenberg’s chief concern seems to be that children in a part-time/synagogue educational program (as he notes, “left of Modern Orthodox”) aren’t learning to read Hebrew, which begs the definition of three different skills – reading (which is gaining meaning from the printed page), decoding (which is what I think the author really is talking about – letter > vowel > letter, etc., with no understanding) and reciting (chanting or singing from memory). The science of reading explains that one learns to read

In our part-time synagogue settings, our children do not have enough background or time to learn to read Hebrew or even achieve the thousands of sight words they have in English. Over the decades, synagogues have tried to create smooth decoders, but really, if one can only decode prayers and blessings (or even Haftarah, as the author would like to achieve), one cannot stay up at synagogue speed. Really, it is hard to smoothly read (or self-correct after trying to decode) siddur words like במשמרותיהם or לבבך because these are not words children instantly recognize in everyday language. To pray at synagogue speed, one has to have put the prayer/blessing in memory and then use the print to follow along. I suspect that a native Hebrew speaker who is in 4th grade or even 6th would stumble when asked to “read” the siddur or Torah; the vocabulary and structure aren't known to them. While Hebrew learning is important, I would argue that the way we have been teaching Hebrew in our part-time/synagogue settings has held the curriculum hostage. In some places, we have dedicated many more hours to Hebrew prayer practice than we have to focusing on the big, compelling ideas of Judaism. Hebrew decoding is a skill, but it doesn’t always touch the heart nor help learners grow and “become” in dialogue with Jewish tradition. In the last five years, a new model for Hebrew learning has been spreading across North America. Called #OnwardHebrew, synagogues and part-time programs that have adopted this approach spend years introducing their learners to the sounds of Hebrew, before moving to print. Children learn vocabulary with Hebrew Through Movement (HebrewThroughMovement.org) – an adaptation of the Total Physical Response (TPR) approach that is used to introduce vocabulary of holidays, rituals and prayers/blessings. They are also gain a rich collection of Jewish Life Vocabulary in context – “grab your siddur, we are going to t’fillah” is just one example. And, they pray regularly in Hebrew, learning to chant/sing t’fillot, thus placing words/phrases in memory. Unlike the decades old “traditional” model of learning Hebrew in part-time/synagogue settings, decoding isn’t introduced early, but rather later (often in 5th or 6th grade) which means that learners can take the sounds of Hebrew in their head and attach them to the print on the page. These older children are more experienced and motivated learners – learning moves relatively quickly and seems to stick. Teachers and educational leaders in #OnwardHebrew programs tell us that there is energy and excitement around learning Hebrew in ways they hadn’t previously experienced and that their children show both confidence and competence. Success is expressed differently from what the author of the Sapir Journal article has defined. Our programs have moved Hebrew learning from a bounded time (e.g., Sundays 9:15-10:15 and Tuesdays at 4:30) to one that creates a rich Hebrew environment throughout the time children are with them. And they are able to shift their focus from “Hebrew School” (check out this CASJE research study titled, "Let's Stop Calling it Hebrew School") to programs that create compelling Jewish learning, broadly defined. I'll end with two resources for those desiring to learn more about decoding with an #OnwardHebrew context. For a powerful webinar that provides a great overview, click here: https://youtu.be/0ayl0i0XpLA. For a webinar segment that explores why we are having trouble with Hebrew learning in part-time/synagogue programs and how the “science of reading” might influence changes, click here: https://youtu.be/zBX0Kz8DfJg?t=1487 Want to know more? Feel free to join the conversation on the #OnwardHebrew FB group. By Barb Shimansky, Director of the School for Living Judaism, Temple Beth Sholom, Miami Beach, FL  When we decided to adopt the #OnwardHebrew philosophy at Temple Beth Sholom in Miami Beach, Florida for the 2018-2019 school year, we knew this would be a shock to the system. Hebrew had been taught in a “traditional Hebrew School” manner for decades. Classes were held twice a week for grades three through six, and learners spent most of this time sitting at tables and going around the room to read lines from primers and workbooks. There would be occasional deviations for things like holiday vocabulary. Learners were certainly learning to read Hebrew, but they were uninspired and unengaged. The relatively new #OnwardHebrew approach changed both the methodology and the narrative by which Hebrew could be taught, and we eagerly jumped “all in.” That is not to say that our constituents were necessarily so eager. Although there was expressed desire for our learners to have a more enjoyable experience, parents were generally uneasy about the idea of their children learning Hebrew differently. While I anticipated this, the pushback was pretty intense during the first year or two. The summer before we launched, a parent called me and said, “I have some questions for you about this Hebrew School where you won’t be teaching Hebrew anymore.” Caught somewhat off-guard, I took a moment before responding, “We will still be teaching Hebrew. It will just be done differently from how we have been doing it.” It turned out that it was not just this one parent who had the impression that we were abandoning Hebrew altogether. This was the rumor going around the community! I realized we needed to communicate differently if our families were going to buy-in to this approach. I will freely acknowledge that the change in my language around this was not one that occurred overnight. In fact, I continue to think about this and continually refine it. Perhaps the most effective thing I can emphasize it that I talk about what we DO, not what we DON’T do. I offer here some of the main points that I try to emphasize when speaking to parents. Overall Philosophy

Framing these conversations with parents in the positive and maintaining ongoing communication with them about what is happening with Hebrew education have been invaluable tools in elevating the success of #OnwardHebrew in our setting. I hope these tips and examples can be helpful to you, regardless of where you are in the #OnwardHebrew journey!  Are you "just curious"about #OnwardHebrew or are you ready to initiate a change process in your educational program? No matter your answer, the relatively concise list of curated resources, below, will help you more easily gather background information and begin plotting your change process: This is a blog post that offers a pretty comprehensive (but quick!) overview of #OnwardHebrew. Of special interest is a chart towards the end that shows in one synagogue the impact on decoding of less years and less hours for Hebrew learning in a synagogue setting (spoiler alert – the learners did just as well with fewer total years and hours!). This is the video that got #OnwardHebrew started - it explains why we have been having issues with Hebrew learning in part-time/synagogue settings. This video is a good conversation starter for faculty, committee members and parents. Much has happened in the world of Hebrew learning since it was created (2013), but its foundation is still solid. This is a webpage with targeted resources for learning about each of the elements of #OnwardHebrew. All are videos, some are webinar-length and others are shorter. For links to many more resources, click on any of the icons on this webpage. This is a "getting started" booklet that offers background on #OnwardHebrew for those who have been curious about the initiative, but not sure where to begin. A special feature is the use of QR codes for those who want more info on a topic than is on the page. This is our blog. All the postings are relatively short and help you gain a broader understanding of #OnwardHebrew. There are a number of postings that would open conversation among stakeholders. This offers an interesting set of reactions to #OnwardHebrew implementation by education directors who have taken on the initiative in their own program. They talk about successes, as well as challenges. This is an article that explores the question of why an educational program might change the grade level in which it teaches decoding. In a traditional Hebrew program, children are introduced to Hebrew decoding in third or fourth grade. However, one of #OnwardHebrew’s innovations is moving the teaching Hebrew decoding to fifth grade or later, after children have built a repertoire of Hebrew sounds and vocabulary. [Feel free to check out this decoding resource developed for #OnwardHebrew's older learners called Let's Learn Hebrew Side-by-Side. In a one-on-one setting, children quickly and easily build decoding skills working sound-to-print.] That said, teaching decoding later is not a requirement for #OnwardHebrew participation; currently, about half of the #OnwardHebrew programs have not shifted their grade level for teaching decoding. NOTE: The decoding article linked here is one of many blogposts on the #OnwardHebrew website, most of which would make for interesting reading and conversation with faculty, clergy and volunteer leadership. Scroll through to see what else interests you!] This is the recording of an American Conference of Cantors webinar with Cantor Leigh Korn (previously the head of the ACC) and Rabbi Nicki Greninger - they are both at Temple Isaiah in Lafayette, CA and have worked for years with #OnwardHebrew's philosophy and elements. Your cantor or clergy team may find this a helpful resource. These are the results of a survey done in summer 2019 with the congregations involved in #OnwardHebrew at the time. Results are in infographic form and may be of use to you, your committee, and possibly teachers. This is a list of assumptions for teaching Hebrew in the 21st century - it would make for good discussion with your committee and/or teachers. This is an edited video of Simon Sinek’s “Start with Why” TedTalk. A good place to begin a change process is to consider “why Hebrew” … like, why is Hebrew important to your host institution or educational program? As Simon Sinek says, “People don't buy what you do; they buy why you do it. And what you do simply proves what you believe.” So what are your bigger purposes to Hebrew learning and use? Your “why statement” will provide a touchstone for continued conversation and course correction over the years. Click here and here for some thoughts on why Hebrew. Finally, while this may seem like a bit of a non sequitur, it’s a helpful resource for those involved in a change process. If you are the kind of educator who likes to start meetings with text study, the Experiment in Congregational Education (ECE) assembled some great Jewish text study resources for change processes. You’ll find them here. A caveat: In many, the Hebrew font used appears in an unintelligible symbol-font – if you wish to use the Hebrew (of course you do!) you may need to grab a printable version of each text from a resource like Sefaria. ## So, are you ready to explore or are you ready to start? #OnwardHebrew is here to help. Please post your comments, questions and additional resources below and/or on the #OnwardHebrew Facebook group. Also, let me - Nachama Skolnik Moskowitz ([email protected]) - know that you are dipping your toes in the #OnwardHebrew waters. I would be happy to offer supports along the way!  eJewishPhilanthropy, December 18, 2019 A long-standing assumption at the heart of synagogue Hebrew education is that if our children learned to read English, it should not be that hard for them to learn to read Hebrew fluently. Yet, even with four years or more of “Hebrew school,” young learners struggle with prayers and blessings. The culprit is often identified as lessened days/hours of learning time or competing family priorities. But, consistent and well-replicated reading research offers us another possibility – countless studies conclude that reading fluency is “… a by-product of having instant access to most or all of the words on the page.” Instant access. Stop and consider your own experience with English as you read the words in this article – you are not decoding letter-vowel-letter-vowel-letter, but rather are instantly and accurately reading each word with understanding. You could do so even if you saw words out of context. For the most part, your fluent reading of tens of thousands of English words was not developed through the use of flashcards, drills or re-reading (“hmm, not quite right … practice reading that again three more times”); none of these skill-based activities create fluent readers. What does? When beginning English readers decode (i.e., sound out) the word p-o-n-y they already know how it is pronounced and have a clear understanding of its meaning. Early English readers can self-correct, if necessary (“oh, that’s not ‘poony,’ it’s ‘pony!”) and then understand the sentence in which it is embedded. Moreso, native language reading research reports that readers turn new-to-them words on a page into instantly accessible sight words via a self-taught and subconscious process that depends on three factors:

By second grade, a typically developing student who meets the three factors above in her native language needs only 1-4 times of decoding a word to store it in memory as a sight word that can be instantly and accurately identified, even if out of context. What does this mean for synagogue education? Unfortunately, it suggests that we set the majority of our Hebrew learners up for failure when “fluent and accurate reading of prayers” is a stated goal. New-to-Hebrew students usually have little idea of the pronunciation (never mind the meaning) of the complex Hebrew words in most Jewish prayers and thus cannot self-correct when decoding. The reading research noted above suggests that unknown words cannot become a fluently-read sight word because the learner does not have the foundation to achieve instant recognition. Not surprisingly, a person who only can decode Hebrew – especially at the halting pace of many new learners – cannot read prayers at synagogue-speed. Yet, we know of young Jews who competently daven. How? These children have stored Hebrew prayers and blessings in memory through multiple exposures to authentic worship. They recite prayers and, if paying attention to the siddur, can match the sounds in their heads to the print on the page. They pray sound-to-print, much like very young children who learned to orally recite entire picture books and then later use known letters to unlock the print on the page. The bonus comes when Hebrew teachers scaffold sound-to-print learning, giving children the foundation to more easily tackle decoding with stronger skills and confidence to self-correct. More so, the originally unfamiliar Hebrew has the possibility of snapping into memory for future access. Based on what researchers tell us about the factors that enable fluent reading, it is time for synagogue educators to reconsider their learning goals and teaching techniques – we cannot expect our learners to achieve Hebrew reading fluency as they have with English. While the native language reading research does not speak directly to our settings, it suggests that

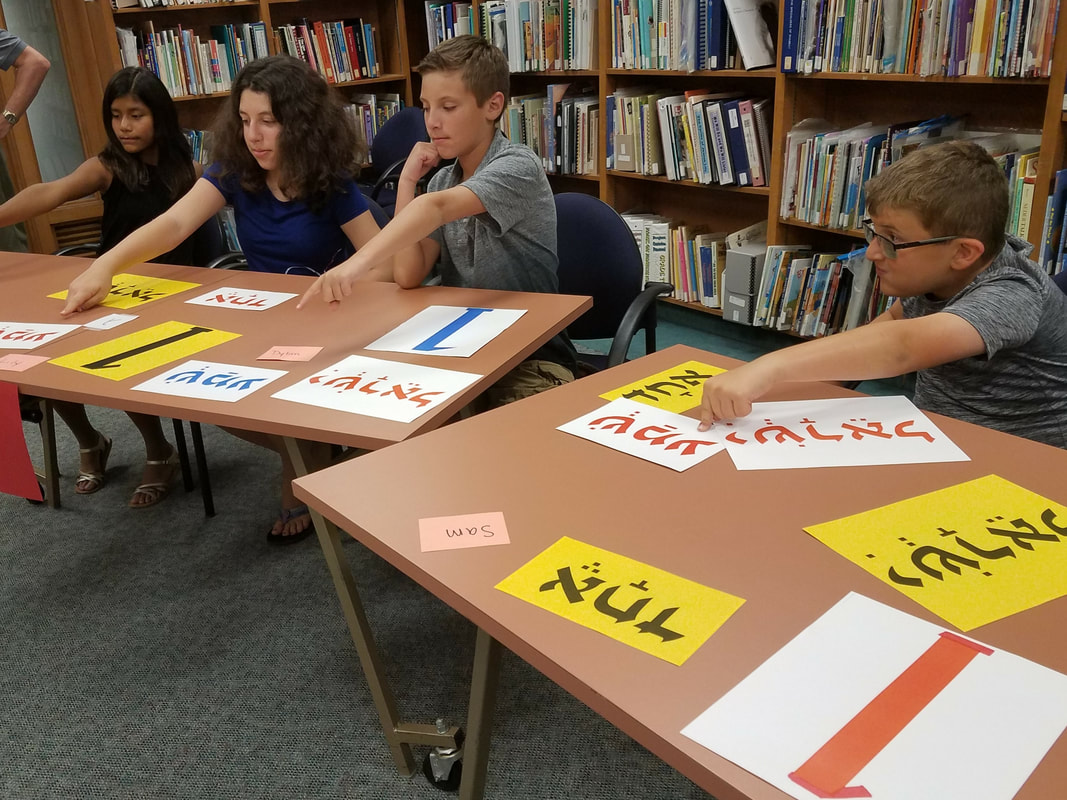

Bottom line, we must more strongly and intentionally honor the sound-to-print progression of learning to read in one’s native language, while paying attention to our unique circumstances. It is true that our pre-bar/bat mitzvah Hebrew learners will never have at their disposal the benefits they had prior to learning to read English – a rich environment in which they heard, responded to and spoke the language before introduced to print. For a whole host of reasons, it would be unusual for our learners to reach the level of fluent Hebrew reading that they have achieved with English – i.e., instant and accurate recognition of a word out of context. To suggest that our students can become fluent Hebrew readers sets them, their teachers, parents and the system up for frustration, even failure. But in the time we have, can we help learners become competent and confident with synagogue Hebrew? Absolutely! By attending to research, rather than our kishkes, we can shift Hebrew learning in our part-time/synagogue settings to more closely honor what the experts tell us. When we do that, it doesn’t have to be hard! Want to know more? Join the conversation with #OnwardHebrew, an initiative that champions better Hebrew learning for students in part-time/synagogue settings. Want more details about the reading research and its application with Hebrew learning? View this webinar segment and then check out some compelling articles. #OnwardHebrew! Join the conversation! To access the article in its original, click here.  by, Nachama Skolnik Moskowitz Lots of links below! Click on the underlined words and phrases! We live in a time when decades old assumptions about Hebrew and Jewish learning in synagogue/part-time settings are being turned on their head. The time devoted to formal learning has been decreasing and many alternative models have moved from “pilots” to “givens.” As noted in a number of recent articles, #OnwardHebrew is transforming Hebrew learning in part-time/synagogue settings across North America – introducing aural Hebrew language via Hebrew Through Movement, Jewish Life Vocabulary, and regular t’fillot, before teaching Hebrew decoding/reading in the year or two prior to Bar/Bat Mitzvah. There is no doubt that children can learn the Hebrew phonetic system in second or third grade; they have been doing it for decades. However, for too many young students, frustration starts mounting in the year immediately following the introduction of the letters and vowel signs, not because the children are not smart enough and not because their brains can’t figure out phonics in a system that uses different symbols. They face three key challenges: decreased time, lack of foundational knowledge and diminished motivation. DECREASED TIME: Over the last 10-15 years, the days and hours per week for Hebrew learning has decreased in part-time/congregational programs across North America. There is no doubt that this structural change demands a rethinking of Hebrew goals, learning assumptions and approaches. From just the standpoint of time, it does not seem realistic to ask our students to achieve the same goals as earlier generations who had many more hours per week and year. In our part-time settings, we simply do not have time to teach communicative language, nor writing, nor reading for meaning. On the other hand, we can offer rich and engaging Hebrew learning opportunities. LACK OF FOUNDATIONAL KNOWLEDGE: Early English readers who confront the printed word “cat” will sound it out “c-at” and realize that they have heard the word many times before, can pronounce it accurately and know what it means. It is a lightbulb moment! On the other hand, children learning to decode Hebrew who confront the printed word בִּמְרוֹמָיו can get stuck (“Bimmm... wait, is that third letter a D sound or an R? Is that an ‘oh’ in the middle, or is that an ‘oh’ at the end?”). Thus, #OnwardHebrew’s push to delay decoding is to offer years during which students can build foundational knowledge, i.e., aural/oral repertoire of Hebrew prayers, blessings and general vocabulary. The word בִּמְרוֹמָיו, when found in context of עוֹשֶׂה שָׁלוֹם (oseh shalom) becomes an easy sound-to-print progression just like the word “cat” was all those years ago. The student recognizes the phrase/word from having participated in many worship experiences and can pronounce it accurately. If students were lucky enough to learn the meaning of Oseh Shalom’s key words via Hebrew Through Movement, they will also have a context for understanding its meaning. DIMINISHED MOTIVATION: An eight year old is often excited to enter the “club” of those who learn to read Hebrew. However, years of “the same, the same” – even with great textbooks and creative teachers – can wear down the early excitement, creating diminished motivation. On the other hand, students who are a year away from their Bar or Bat Mitzvah bring a maturity for the learning process and stronger motivation for achieving performance goals. In a one-on-one setting, they can learn to decode/read Hebrew letters and vowel signs in 12-15 hours, followed by the normative number of meetings his/her synagogue requires with a B’Mitzvah tutor. So, rather than spending years of Hebrew and prayer rote practice, #OnwardHebrew’s compacted approach for learning Hebrew builds foundational knowledge while suddenly opening up time for more compelling Jewish learning. In an era where Jewish educators talk about Jewish learning for “thriving” and “meaning-making,” transforming the Hebrew learning approach has the potential to benefit the entire Jewish educational enterprise. A few words of advice from those who have been down this path: JOIN THE CONVERSATION: Learn as much as you can by grabbing a cup of coffee (or ice cream!) and then spending an hour or so on the #OnwardHebrew site, clicking on articles and videos. Join the #OnwardHebrew Facebook group, paying attention to the postings; feel free to ask questions or offer your own comments. EXPAND THE CONVERSATION: Stir #OnwardHebrew conversations among stakeholders – clergy, teachers, committee and board members – by sharing and discussing the articles and videos you feel would resonate. PICK SOME LOW HANGING FRUIT: With your stakeholders, decide if you are ready to pilot one or more of the #OnwardHebrew elements – Hebrew Through Movement (make sure your teacher(s) sign up for the online seminar!) Jewish Life Vocabulary (LOTS of resources here – keep clicking around!) and Hebrew t’fillot. Each of these easily complements any of your other current Hebrew learning goals, curriculum or textbooks. Keep in mind that there is potential crossover between these elements. For example you can anchor JLV in the Hebrew alef-bet, introducing one letter a week and teaching two to three Hebrew words that start with it. Thus, a child in your program from first grade onwards would have had six years of seeing most of the letters prior to learning to decode. OR, integrate Hebrew sight words into your Hebrew Through Movement lessons (the picture on at the bottom of this blogpost is from an HTM lesson on Sh’ma). Taken together, #OnwardHebrew’s low hanging fruit are examples of rich Hebrew learning, even without the introduction of decoding until children have gained years of Hebrew vocabulary. CONSIDER WHEN TO TEACH DECODING: Do not rush this decision - it takes open conversation with stakeholders (clergy, parents and teachers), as well as the implementation of some experiments or pilots. For example, consider experimenting with “Let’s Learn Hebrew Side-by-Side” for any children who enter your program in fifth or sixth grade not having yet learned to decode/read Hebrew. Or, exchange traditional letter recognition learning in K, 1 and 2, with Hebrew Through Movement. Or, follow the lead of some educational programs that remove decoding from second and third grade with a target grade of where they will introduce it later (e.g., fifth grade), but keep open the possibility of changing that time of introduction. And be sure to evaluate the process and results when done! # # # Kol hakavod for considering the question! Stay in touch with the #OnwardHebrew if you need help! The "Contact Form" is a great way to connect in. Want to share this post? A PDF of this posting is below.

|

AuthorSAll of us! If you have something to contribute, send your posting via the Contact webpage! Archives

September 2023

Categories

All

|

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed