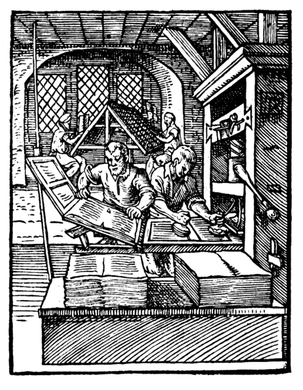

Recently, I’ve been thinking about Gutenberg’s printing press and its harsh impact on Hebrew School. And indeed, initial drafts of this blog post began as a tirade against Gutenberg, blaming him for the struggles of many a child in Hebrew School. For if he hadn’t invented the ability to print prayerbooks in mass quantities, then worshipers wouldn’t have books in their hands, and Jewish children would not have to struggle with learning to decode Hebrew over four to six years in the learning environment known as “Hebrew School.” Yikes! It got a little complicated as I realized I couldn’t blame Gutenberg alone – the Enlightenment, Industrial Revolution and a host of other factors could also be implicated in the path to creating the current model of Hebrew learning in part-time/congregational settings. But here’s the point – two thousand years ago, Jewish prayers were shared orally, not slogged through by those learning to decode Hebrew. In the days of scribes and scrolls, an inspirational person who understood the structure of traditional worship led the community in a strong, clear voice. The people could and would do any number of things: listen, recite along with the worship leader, repeat lines or simply say amen. Prayer was an outpouring of the heart that transcended the printed page … oh, wait, there was no printed page at that time! The first written prayerbook was a letter sent by one rabbi to the community of Barcelona in the 9th century CE, and it was not until the mid-15th century that Gutenberg’s printing press made it possible to more easily duplicate copies of books. BUT, over the last few decades, we as Jewish educators have twisted ourselves into tight knots teaching our students what we assume is the one and only way to pray – book in hand, eyes following the print on the page, and using skills of decoding to stay up with the service. And how do we know (hmm, test) that students can participate comfortable in Hebrew worship? Often prior to b’nai mitzvah tutoring, someone checks their reading fluency by handing them a piece of Hebrew text that they have never seen before and asking them to read aloud. Many children struggle, some cry. Most of us learned to read as a young child because over five to six years of listening and eventually talking, we built an incredibly large vocabulary and kishke-understanding of English’s structure. A child who sounds out c-a-t often has a light bulb moment – “Oh wait, I know that word! Cat!!” But children who are asked to sound out Hebrew prayer words they don’t know and may never understand because of adult-complexity and prosaic structure (like בְּמִשְׁמְרוֹתֵיהֶם) are caught like deer in the headlights. The “I-know-that-word!”-light-bulb-moment never comes. #OnwardHebrew suggests that we go back to our roots, introducing new learners to Jewish prayer orally, without concern that they have memorized the text (oh my!) before being able to relate to the printed page. Competent and confident pray-ers are not defined by “decoding to synagogue speed with two or fewer mistakes.” In fact, it’s rather impossible to decode to synagogue speed; one HAS to have the prayers and blessings in one’s head and heart (a softer way to describe “memorize”) to stay up with the service. Besides emphasizing the singing or reciting of Hebrew prayers and blessings in t’fillah (worship), #OnwardHebrew also suggests spending years of building the sounds of Hebrew language in the hearts of our learners in other ways – Hebrew Through Movement (a fun, kinesthetic way to learn key vocabulary of holidays, prayers and blessings) and Jewish Life Vocabulary (Hebrew words that are integrated into English sentences – “What a sneeze! Labri-ut!” or “Grab your siddur, we are going to t’fillah”). Children closer to the age of bar/bat mitzvah who have richly built the sounds of Hebrew can quickly and easily learn the Alef-Bet (12-15 hours) and then match this new skill with the words and phrases now gloriously floating in their heads (oh, yes, and hearts). While I’ve moved on from blaming Gutenberg, I yearn for a return to the days of scribes, scrolls and the aural/oral learning and transmission of prayers and blessings. I challenge us as Jewish educators to release ourselves from the decades old (not millennia old) tradition of teaching in which our students often painfully decode prayers and blessings, syllable-by-syllable, word-by-word. No, I am not suggesting that we skip teaching Hebrew decoding/reading altogether. But for the sake of our young learners, I am pushing us to become more savvy about the process and more efficient with our time. If we can affect this change in our curriculum, releasing our students from years of frustrating work with pre-primers, primers, prayers and blessings, then amazingly we will have more time for engaging, meaningful and compelling Jewish learning ... which is what the Jewish educational enterprise should be about! #OnwardHebrew!! Join the conversation here (comments are welcome, below) and on Facebook! Kol tuv ("all the best") <<just a little Jewish Life Vocabulary thrown in! Nachama Skolnik Moskowitz, Director of Curriculum Resources Jewish Education Center of Cleveland

3 Comments

7/5/2018 09:01:03 am

Yes, of course you are right. And we should not forget the role of music in helping to achieve rote learning of the texts.

Reply

Nachama Skolnik Moskowitz

8/14/2018 10:30:37 am

Thanks for your note, Jonathan! We're on the same page with this. I appreciate you sharing your materials. The #OnwardHebrew Jewish Life Vocabulary page is here https://www.onwardhebrew.org/jewish-life-vocabulary.html (you may already have found it). Nachama

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorSAll of us! If you have something to contribute, send your posting via the Contact webpage! Archives

September 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed